Quranic Answer

The Holy Quran, as a comprehensive guide for human life, places immense emphasis on the psychological and social well-being of individuals and communities. One of the most crucial ways to achieve this well-being is by maintaining purity and honesty in speech. Consequently, the Quran explicitly and unequivocally prohibits various forms of gossip, backbiting, tale-telling, and any other harmful speech that leads to the deterioration of human relationships and the erosion of trust within society. These prohibitions are not mere ethical recommendations but divine commands, meticulously designed to foster a healthy, trustworthy, and compassionate community. The profound divine wisdom behind these injunctions recognizes the immense damage that an unchecked tongue can inflict upon individuals, families, and the entire social fabric. The tongue is a powerful instrument that can be used for both construction and destruction, and the Quran insists that humans utilize this blessing for good and avert its potential harm. One of the most explicitly condemned forms of 'sokhan-chini' (a broad term encompassing various types of harmful speech) is Gheebah (غيبة), commonly translated as backbiting. This refers to speaking ill of a person in their absence, mentioning something about them that they would dislike to hear, even if that characteristic or fault is true. The Quran vividly illustrates the severity of this act with a powerful and repulsive metaphor in Surah Al-Hujurat (49:12): "O you who have believed, avoid much [negative] assumption. Indeed, some assumption is sin. And do not spy or backbite one another. Would one of you like to eat the flesh of his brother when dead? You would detest it. And fear Allah; indeed, Allah is Accepting of repentance and Merciful." This verse likens backbiting to eating the flesh of one's dead brother – an imagery designed to evoke extreme disgust and highlight the repugnance of the act. Just as a deceased person cannot defend themselves, an absent individual cannot defend their honor or clarify misconceptions. Backbiting is a profound violation of trust, an unwarranted attack on personal dignity, and a corrosive force that systematically erodes the bonds of brotherhood and sisterhood within the community. It chips away at a person's reputation, even if what is said is true, because it involves exposing private matters or flaws that are not meant for public discourse, especially in a negative light. The verse also links backbiting to suspicion (su' al-dhann) and spying (tajassus), indicating that these are often precursors to backbiting. Unfounded suspicions can lead to spying, which then frequently results in the spread of discovered or even fabricated faults. Another distinct and severely condemned form of 'sokhan-chini' is Namimah (نميمة), meaning tale-telling or carrying malicious gossip between people with the explicit intention of sowing discord, creating enmity, or breaking relationships. It involves transferring words from one person to another to harm the original speaker or the listener, or to incite strife. The Quran warns against such individuals in Surah Al-Qalam (68:10-11), describing them as highly blameworthy: "And do not obey every [worthless] habitual swearer, a backbiter, [who is] a malicious gossip-monger." These verses explicitly caution against obeying those characterized by excessive swearing, being contemptible, being a fault-finder, and specifically, 'mushsha'in bi namim' (those who go about with calumnies). Namimah is arguably even more destructive than gheebah in some respects because its primary aim is to incite conflict and hatred among people. It often involves fabricating or exaggerating information to turn individuals against each other, whether among friends, family members, or even entire communities. Such actions utterly destroy social cohesion and trust, making it impossible for people to live together peacefully and cooperatively. The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) also emphatically highlighted the gravity of namimah, stating that a tale-teller will not enter Paradise. Furthermore, the Quran denounces Hamz (همز) and Lamz (لمز), which refer to slandering, defaming, finding fault, and ridiculing others, whether through words, gestures, or insinuations. Surah Al-Humazah (104:1) unequivocally states: "Woe to every backbiter and slanderer." 'Humazah' refers to one who slanders or finds fault with others through actions or gestures (e.g., eye gestures, body language, mocking looks), while 'Lamazah' refers to one who slanders with words, verbally abusing or deriding. Both terms underscore the act of diminishing or belittling others, often with malicious intent. These actions strip individuals of their dignity and self-worth, leading to humiliation and psychological harm. This form of 'sokhan-chini' fundamentally undermines mutual respect and compassion, which are foundational principles of Islamic social conduct. It fosters an environment of negativity where people feel constantly judged and scrutinized, rather than supported and understood, thereby stifling genuine interaction and affection. Beyond these specific terms, the Quran consistently promotes a general principle: to speak good words or to remain silent. It encourages believers to maintain virtuous speech, avoid vain talk, and speak justly. Any speech that is false, deceptive, or intended to cause harm, division, or discord is implicitly or explicitly forbidden. The overarching message is unequivocally clear: the tongue is a potent tool that can be wielded for either good or evil, and believers are divinely commanded to use it for constructive purposes – for spreading truth, promoting good, strengthening communal bonds, and offering comfort. Engaging in 'sokhan-chini' in any of its myriad forms is a direct contravention of these divine commands, leading inevitably to spiritual decay, societal breakdown, and divine displeasure. Such acts poison the atmosphere of trust, compassion, and mutual affection that Allah desires for His servants. The Quran repeatedly calls for truthfulness, justice, and kindness in speech, making any deviation from these principles a matter of grave concern. The comprehensive prohibition of 'sokhan-chini' is thus a profound testament to Islam's unwavering commitment to building a virtuous society where dignity, respect, and mutual affection prevail over malice, discord, and unfounded accusations.

Related Verses

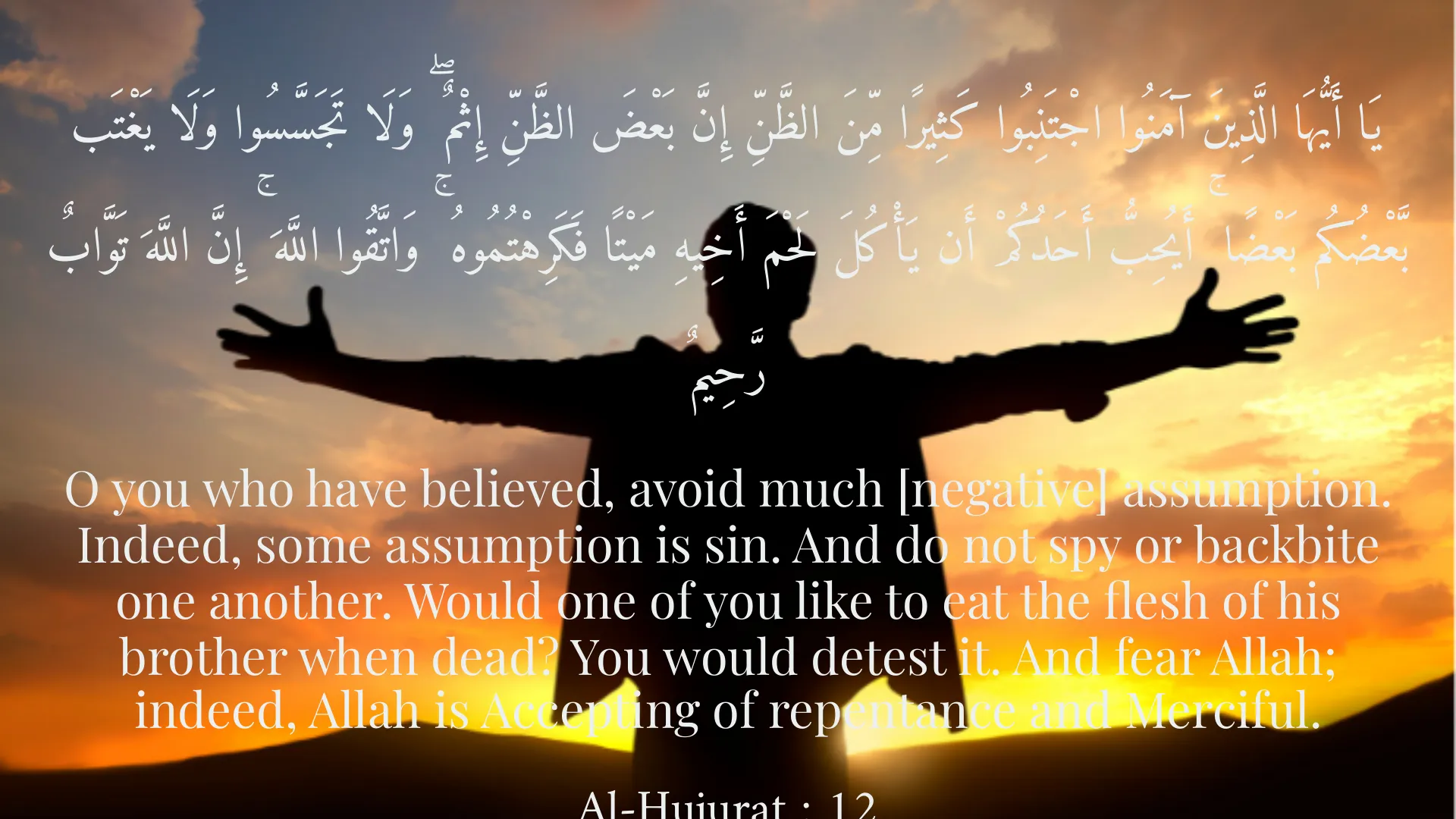

يَا أَيُّهَا الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا اجْتَنِبُوا كَثِيرًا مِّنَ الظَّنِّ إِنَّ بَعْضَ الظَّنِّ إِثْمٌ ۖ وَلَا تَجَسَّسُوا وَلَا يَغْتَب بَّعْضُكُم بَعْضًا ۚ أَيُحِبُّ أَحَدُكُمْ أَن يَأْكُلَ لَحْمَ أَخِيهِ مَيْتًا فَكَرِهْتُمُوهُ ۚ وَاتَّقُوا اللَّهَ ۚ إِنَّ اللَّهَ تَوَّابٌ رَّحِيمٌ

O you who have believed, avoid much [negative] assumption. Indeed, some assumption is sin. And do not spy or backbite one another. Would one of you like to eat the flesh of his brother when dead? You would detest it. And fear Allah; indeed, Allah is Accepting of repentance and Merciful.

Al-Hujurat : 12

وَلَا تُطِعْ كُلَّ حَلَّافٍ مَّهِينٍ

And do not obey every [worthless] habitual swearer,

Al-Qalam : 10

هَمَّازٍ مَّشَّاءٍ بِنَمِيمٍ

a backbiter, [who is] a malicious gossip-monger.

Al-Qalam : 11

وَيْلٌ لِّكُلِّ هُمَزَةٍ لُّمَزَةٍ

Woe to every backbiter and slanderer.

Al-Humazah : 1

Short Story

It is said that in ancient times, in a prosperous city, there lived two neighbors: one named Nasseh, a calm and wise man, and the other named Qil-o-Qali, whose tongue never ceased from gossiping and recounting others' words. One day, Qil-o-Qali heard an unseemly remark from one of the city's dignitaries and, without delay, exposed it among the people, adding embellishments of his own. This remark, like a spark in dry straw, quickly ignited the flames of discord, creating great resentment between the people and the dignitary. Nasseh, witnessing this, approached Qil-o-Qali and, with a friendly smile, said: 'My brother, your tongue is sweet, but know that speech is like a two-edged sword; it can plant a rose or a thorn. Saadi says: 'Until a man has spoken, his fault and virtue remain hidden.' If you remain silent, you will be safe, and if you speak good words, you will become beloved by hearts. But tale-telling destroys friendships and pains hearts.' From that day on, Qil-o-Qali reflected and strove to use his tongue only for good, and thereafter, peace and tranquility returned to homes and hearts.